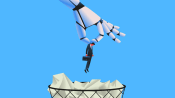

Commentary: Companies are getting worse at laying people off

Businesses sometimes need to retrench employees. But that doesn’t mean those cuts need to be sloppy or cruel, says Beth Kowitt for Bloomberg Opinion.

NEW YORK: The latest jobs numbers in the United States may have shown a drop in the number of pink slips hitting workers’ desks in May, but don’t be fooled: Layoffs are alive and well in 2025.

In the first half of the year, US employers let go of nearly 745,000 people, according to outplacement firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas. That’s the second-highest number for the period since 2009 – surpassed only by the first six months of 2020, when COVID-19 essentially shut down the global economy.Â

The cuts are part of a broader trend. About 20 per cent of S&P 500 companies have fewer employees today than they did a decade ago, according to a recent Wall Street Journal analysis.

Yet even after years of practice slashing payrolls, most companies are still shockingly bad at it.

SUCKING THE HUMANITY OUT OF LAYOFFS

In fact, it’s the frequency and volume of workforce cuts that seem to be making them even worse; normalising the practice has ended up sucking the humanity right out of it.

Case in point: dating app Bumble, which last week announced that it was laying off 240 employees, 30 per cent of its workforce. When employees, who received the news via video call, responded with thumbs-down emojis, founder and CEO Whitney Wolfe Herd told them: “Y’all need to calm down,” adding, “Everyone’s going to have to be adults in dealing with this.”

I’m not sure what kind of response Herd expected. A thumbs-down is a much more work appropriate alternative to the digit they could have thrown her way – especially considering what we know about the impact layoffs have on both those let go and those left behind. (My colleague Sarah Green Carmichael has written extensively on these detrimental effects.)

Also last week, executives at Microsoft showed their own flavour of callousness when they announced they would lay off 9,000 workers. That’s on top of the 6,000 the company laid off in May.

That Microsoft couldn’t figure out the total number it would need to cut two months earlier suggests both sloppiness and thoughtlessness. Layoff survivors will now live in a constant state of anxiety that additional downsizing could be right around the corner.

A SMALL PERCENTAGE CAN STILL BE THOUSANDS OF PEOPLE

AI has only made matters worse. It’s become a justification for layoffs, while also letting companies outsource the work of empathy to an LLM.

An executive producer with Microsoft’s Xbox, which was heavily impacted by the cuts, wrote a LinkedIn post offering some AI prompts that would “help reduce the emotional and cognitive load that comes with job loss”. He’s since deleted the post.

Microsoft pointed out the most recently announced cuts are less than 4 per cent of the company’s total workforce. That’s still thousands of people, and is the kind of justification Harvard Business School professor Sandra Sucher sees as an increase in “moral disengagement” on the part of CEOs.

She told me the big bosses have become so far removed from the average employee that they “don’t seem to understand what it means for someone to lose their job”. Layoffs are increasingly “stripped of any acknowledgement that harm is being done,” she added.

A CRISIS OF TRUST

It’s the layoff edition of a broader phenomenon I’ve been following among America’s CEOs: the end of the era of corporate do-gooderism and make-the-world-a-better-place discourse.

Empathetic leadership, all the rage during the COVID-19 era, isn’t part of the conversation anymore. And the lack of respect that employees have subsequently felt from their employers is accelerating a crisis of trust in big business.

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg has come to embody this leadership transformation. In 2022, when the company cut 11,000 employees, Zuckerberg – as was the practice of many CEOs at the time – took accountability for poor decision making. “I know this is tough for everyone, and I’m especially sorry to those impacted,” he said.

Fast forward to January 2025, when Zuckerberg said he was cutting about 5 per cent of staff by moving out “low performers”. The blame had been shifted.

There was no acknowledgement of what such a public statement might mean for the future job hunts of those impacted, and certainly no “I’m sorry”. As Zuckerberg has said, he is done apologising.

Layoffs are a reality of corporate America, and they’re not going away. But that doesn’t mean they need to be cruel. As Sucher told me, companies preparing for a cut should have a mantra: for the right reason, in the right way.